Hackers Who Wear the White Hat While Using Black Hat Skills

On a cool morning last May, Jack Cable was playing with his dog in his family’s suburban Chicago living room. When his mother left for work, the soft-spoken 17-year-old opened his laptop, kicked his feet up on the couch, and hacked into the United States Air Force computer system.

It took him about five minutes.

Over the next few weeks, Cable accessed the Air Force system about 30 more times in search of security flaws. Each one he found was incrementally more complex and challenging. A few weeks later Cable got a check in the mail. A nice one, from the U.S. government, thanking him for identifying vulnerabilities in the Air Force system.

Cable is a military-grade hacker and was one of 600 “ethical” or “white hat” hackers invited to “Hack The Air Force” as part of a so-called bug-bounty program. This one was hosted by HackerOne, a bug-bounty platform that connects ethical hackers to help companies find and repair vulnerabilities in their security systems.

It’s one of many bug-bounty initiatives increasingly used in both the public and private sectors where security researchers are encouraged to find and disclose security flaws, often for monetary reward.

Today, almost every major tech company has a bug-bounty program and the industry has steadily increased the size and volume of rewards. In the early days of these programs an ethical hacker might get something as nominal as an online thank you or a few hundred dollars. But today’s bug bounty ecosystem has become big business.

In theory, everybody wins: companies and government agencies avert potentially catastrophic security breaches while hackers are paid for their expertise.

In 2016, Google paid out $3 million in bug bounties. Other major tech companies like Facebook, Uber and Microsoft embraced hacker culture years ago, paying millions to hackers for their expertise. And the numbers seem to be growing at a rapid fire pace. Bugcrowd, a hacker platform, revealed in its State of Bug Bounty report that adoption of bug-bounty programs was up 300 percent last year with total payouts have surpassing $6 million, up 211 percent since 2016.

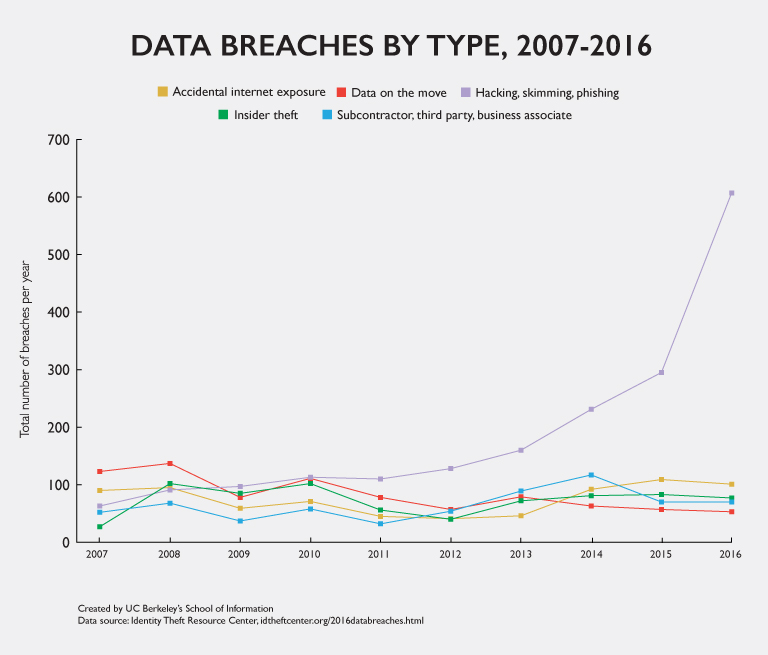

Meanwhile, the Identity Theft Resource Center identified a 350 percent increase in data breaches from 2007 to 2015. The nonprofit’s running list of victims reveals that security breaches are widespread across industries, from health-care providers to multinational banks to the U.S. Air Force. Nearly 85 percent of those can be traced to last year’s breach at Equifax, one of the nation’s three major credit reporting agencies. About 145 million American consumers had their personal information exposed during that massive data breach, and it prompted a class-action suit against Equifax brought on by consumers.

Go to a tabular version of Data Breaches by Type at the bottom of this page.

The Hacker Mindset

Alex Stamos, chief security officer at Facebook and member of UC Berkeley’s CLTC External Advisory Committee, said the company is one of the largest proponents of an innovative cybersecurity culture.

“Our bug-bounty program provides recognition and compensation to security researchers who help us keep people safe by reporting vulnerabilities in our services,” he said. “In addition to looking for security vulnerabilities, we also encourage people to focus on defensive security.”

During a keynote at the Black Hat 2017 conference, Stamos said the “hacker mindset” needs to be celebrated across public and private sectors.

“We are no longer the upstarts. We are no longer the hacker kids fighting against corporate conformity,” he said. “We don’t fight the man anymore. In some ways, we are the man. We have perfected the art of finding problems.”

While bug bounties are growing, money isn’t the only motivation for white hat hackers.

“Recognition is also a big factor,” said Ted Kramer, chief of staff at HackerOne. “They want people to know they found a vulnerability. It’s a badge of honor in the community.”

Bugcrowd recently released another study detailing its 65,000-strong community of security researchers and found that, for most ethical hackers, “the challenge,” not monetary reward, was their top motivation.

Nate Cardozo, an attorney with the digital rights nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation, said hackers are driven by “breaking stuff and making it stronger.” He said by taking part in bug-bounty programs, hackers are often hired to be part of company security teams.

Indeed, bug hunting is a part-time endeavor for most hackers, according to the Bugcrowd report, although 27 percent have aspirations of becoming full-time bug hunters and 62 percent said they invest at least part of the money they earn bug hunting back into their professional development.

Pathway to Cybersecurity

Like many hackers, Jack Cable started young, driven by the challenge of finding security vulnerabilities online and as a way of testing his own hacking skills. When he was 15, Cable stumbled on a security flaw in a bitcoin company. He says he could have transferred a significant amount of bitcoins but he instead reported the security flaw through the company’s bug-bounty program.

“I never thought about profiting from finding those security flaws.” Cable said. “You can’t put ‘stealing from companies’ on your resume.”

Especially when those resumes are in such high demand. More than 209,000 cybersecurity jobs in the U.S. are unfilled, according to a 2015 analysis of Bureau of Labor data by Peninsula Press.

Casey Ellis, founder of Bugcrowd, told Ars Technica that the prevalence of young people using bug-bounty programs “as an on-ramp into the security industry in general” has been consistent since he started the company in 2012.

“Obviously, they’ve got the technical prowess, they’ve got the interest in the offensive side of it, and they want to contribute and make things safer as well,” Ellis said.

Bug-bounty programs are not without their critics who say most bug hunting doesn’t get down to the root of the problem.

“Companies think that bug bounties are simply something they can announce and that will be enough,” Ilia Kolochenko, CEO and founder of the security firm High-Tech Bridge, wrote on his company blog.

Kevin Finisterre, a well-known security researcher recently published a long essay about how he was able to hack into drone company DJI’s servers and gain access to sensitive customer information. Finisterre submitted his findings to DJI as part of its bug-bounty program. The company offered him its highest reward of $30,000, but part of the deal was an assurance of his silence. For Finisterre, recognition was more important than the money, and the negotiations ended in what the hacker considered legal threats.

But for most ethical hackers, the proliferation of bug-bounty programs only confirms the embrace of the hacker mindset.

“Hackers view the world through a different lens than most,” said HackerOne spokesperson Lauren Koszarek. “They’re problem solvers, they’re scrappy and creative, and they stand up for what’s right. They’re not afraid to break the rules if it means getting the job done.”

The following section contains tabular data from the graphic in this post.

Data Breaches by Type, 2007-2016

| Breach Type | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Insider theft | 27 | 102 | 85 | 102 | 56 | 40 | 72 | 81 | 83 | 77 |

Hacking, skimming, phishing | 63 | 91 | 97 | 113 | 110 | 128 | 160 | 231 | 295 | 607 |

Data on the move | 123 | 137 | 78 | 111 | 78 | 57 | 79 | 63 | 57 | 53 |

Accidental internet exposure | 90 | 95 | 59 | 71 | 45 | 41 | 46 | 92 | 109 | 101 |

Subcontractor, third party, business associate | 52 | 68 | 37 | 58 | 32 | 54 | 89 | 117 | 70 | 70 |

Data source: Identity Theft Resource Center, idtheftcenter.org/2016databreaches.html

Citation for this content: cybersecurity@berkeley, the online masters degree in cybersecurity from UC Berkeley School of Information.