Book Review: Freakonomics by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner

If you’re at all interested in economics, data science, or even just popular books, it’s a good bet that you’ve heard of Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner’s 2005 New York Times bestseller, Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything.

In the eight years since its publication, the book has spawned a sequel and even a documentary. Eight years might seem to be a long shelf life for a book about statistics, particularly one dealing with current events, but as one of the first books to push economics and data science into popular consciousness, we think it’s definitely worth taking a second look.

Freakonomics, which weighs in at just over 200 pages (plus a hefty section of bonus material for those interested in learning more), takes as its principal argument the idea that economics exist as a tool to study society.

Steven D. Levitt, the self-described “Rogue Economist” of the title, uses this tool to analyze a random assortment of topics. These include the recent drop in crime in American cities, the possibility of rampant corruption in professional sumo wrestling, and the real impact of parenting on a child’s life outcomes, among others.

In the latter example, data patterns have shown that factors correlated with a child’s test scores include having highly educated parents, a high socioeconomic status, English spoken at home, parents who are involved in the PTA, and a house full of books. Makes sense, right?

On the flip side, however, factors such as a family being “intact,” having parents who read to the child nearly every day or regularly take him or her to museums, having a mother stay at home until the child reaches kindergarten, or even frequent television viewing have been shown to have no impact on a child’s eventual test scores.

These correlations are unlikely to change the habits of many helicopter parents (truthfully, would you stop reading to your child based on stats alone?), but the findings are in keeping with Levitt’s main premise:

“Morality, it could be argued, represents the way that people would like the world to work — whereas economics represents how it actually does work. Economics is above all a science of measurement. It comprises an extraordinarily powerful and flexible set of tools that can reliably assess a thicket of information to determine the effect of any one factor, or even the whole effect. — p. 11

Levitt doesn’t feel that it’s necessary to identify a common theme among the topics he analyzes, explaining that “since the science of economics is primarily a set of tools, as opposed to a subject matter, then no subject, however offbeat, need be beyond its reach.” This statement sounds remarkably similar to data science. In fact, much of the book parallels the experience of modern data scientists.

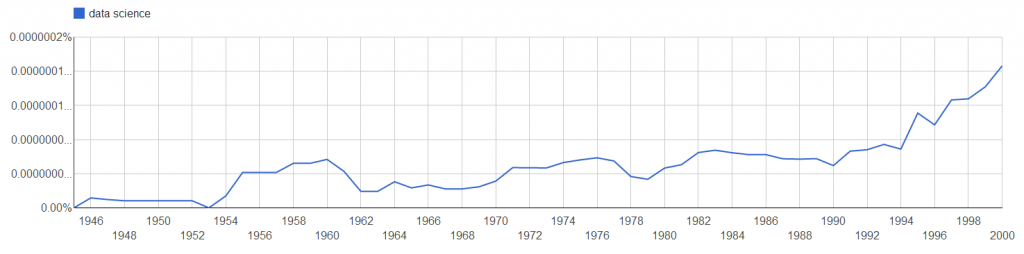

“Data science” is a term that has come to prominence recently (as seen in Google Ngrams search results below), whereas economics as a field has been entrenched in the academy at least since Adam Smith’s work in the 18th century.

The underlying principles are the same, however, at least when it comes to analyzing society. In fact, the tools and trends of Levitt and Dubner’s “economics” map so closely to the experience of data analysis that we’re more than comfortable toting this book as a love letter to the field of data science (as well as other analytical careers).

Levitt and Dubner’s Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything offers some fascinating statistics. The real message, however, is not in the details, but in the overarching picture: the tools of economics (and, in our minds, data science) can be used to identify unexpected patterns in real-world occurrences, but scientists are still needed to interpret these results.

After all, your query of a data set may reveal patterns you couldn’t have predicted (or may not have wanted to hear), but that doesn’t mean they aren’t there. In other words, data sets exist as a static collection of facts, but analysis must include a devotion to “thinking sensibly about how people behave in the real world.”

In keeping with this, Freakonomics espouses these 5 principles:

- Incentives are the cornerstone of modern life.

- The conventional wisdom is often wrong.

- Dramatic effects often have distant, even subtle, causes.

- “Experts”—from criminologists to real-estate agents—use their informational advantage to serve their own agenda.

- Knowing what to measure and how to measure it makes a complicated world much less so.

With these tenets in hand, scientists are much better equipped to understand and explain what their data is trying to tell them.

Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner conclude Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything with a discussion of the point where “the dependability of data meets the randomness of life,” the perfect summation of their theme. Like the storied butterfly flapping its wings in China, “dramatic effects often have distant, even subtle, causes.” Just because we can’t always alter the future based on past data, however, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to understand its lessons.