The Damaging Effects of IP Theft

When New Balance came to China in 1995, it was expecting to leverage the country’s manufacturing benefits to produce shoes at a lower cost. It was not expecting more than 20 years of lawsuits over counterfeit sneakers, trademark violations, and a $16 million court ruling against the company in 2015 (later reduced to around $700,000 on appeal).

At the core of New Balance’s woes across the Pacific was the theft of its intellectual property. The company initially licensed its shoe production to a Taiwanese factory. After the popularity of its “Classic” shoe took off, the factory owner, Horace Chang, wanted to double down on production to meet demand. New Balance disagreed. The factory produced the shoe at an accelerated rate anyway, and New Balance canceled Chang’s contract in 1999. Chang nevertheless continued producing the “Classic” design shoe, but under a new brand name, Henkees.

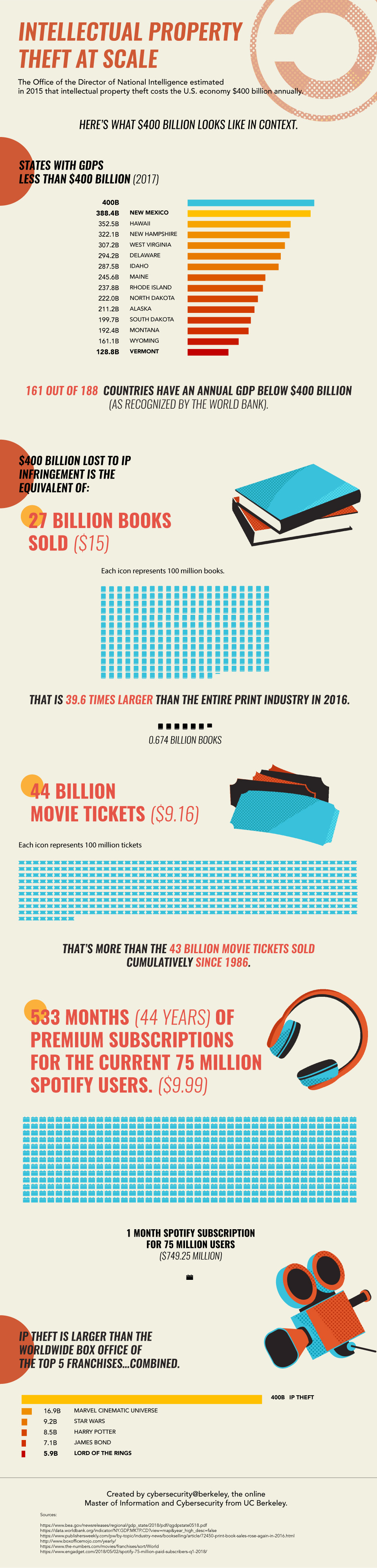

With a global economy conducted increasingly online, intellectual property theft is a growing problem for businesses and policy makers. The problem can be difficult to define and quantify, hard to track, and complicated to enforce. It’s also costly: William Evanina, national counterintelligence executive of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, estimated in 2015 that intellectual property theft costs the U.S. economy $400 billion annually.

What Is Intellectual Property?

Owning intellectual property isn’t like owning something tangible, like a car or a house. The World Trade Organization describes it as rights “given to persons over the creations of their minds,” and that creators are given exclusive rights over the use of their creations.

“It’s difficult to define because it’s not tied inherently to a physical good,” said Steve Weber, a professor at the UC Berkeley School of Information and the faculty director of the Center for Long Term Cybersecurity. Weber defines the idea of property as “something valuable” that a creator “can access or exclude others from access or use in a way that is defensible, either physically or legally.”

Intellectual property doesn’t have to exist in the physical world. Readers can buy a book in a store, but it’s the words and the ideas on the page that are the intellectual property of the creator. Intellectual property can range from song patents to computer software to corporate trade secrets. The designs of tangible goods like a handbag or a watch can also be considered intellectual property.

Difficulties in Enforcement

When New Balance canceled its contract with Chang, he did not return their property, including the molds and production information that would allow him to produce Henkees. New Balance filed an injunction against Chang and his factory in 2000, but a Chinese court ruled in Chang’s favor and even gave him the “implied license to distribute” without paying royalties.

The broadly defined nature of intellectual property and the ease with which it can be stolen, combined with a set of laws that are lax when it comes to enforcement, enabled Chang and others to use New Balance’s intellectual property as their own.

The New Balance case is about a tangible good, but in the digital age, as online products and services become cheaper and more prevalent, intellectual property is increasingly more susceptible to theft.

Ease of Stealing

The Internet has proven to be a transformative communication tool. So much so that “we’ve bootstrapped a lot of our economy to it,” Weber said. But the Internet wasn’t designed with security in mind. Its communicative nature is at odds with how it is used today.

“It was designed as a communication network among a small number of computers that were owned by people who knew and trusted each other,” Weber said. “The underlying technical infrastructure is not designed for what we’re using it for. That doesn’t mean it’s bad or wrong; it just means that it wasn’t set up to make security easy.” Cybersecurity systems are also designed and created to be useable, juggling the technical nature of cybersecurity with the inherent challenges human interaction creates.

The unstable nature of Internet security makes stealing intellectual property easy compared to physical theft. There are digital vulnerabilities that have serious consequences in real life, according to a Quartz article. A digital burglar can steal from a computer on the other side of the world, then copy and distribute the material to a wide audience.

Some companies are combating intellectual property theft at factories producing their own products. In the case of New Balance, the company was initially vulnerable to “Third Shift” production.

Aisha Farraj, an intellectual property lawyer with Powell & Roman in New York, outlines this problem in a 2015 paper, “The Third-Shift Problem in China.”

In Farraj’s example, a company grants a license to another company — called an “original equipment manager” or OEM — to manufacture a specific number of products. A car manufacturer, for example, contracts an auto parts firm to make its crankshafts. The original company shares its intellectual property with the OEM so that it can make the product it’s contracted to make. In the third-shift scenario, the OEM operates its factory after hours, producing an extra shift’s worth of products that it will then sell, illegally profiting from the original company’s intellectual property.

Ease of Anonymity and Leveraging Intermediaries

Discovering that an entire factory is running an extra shift to rip off its licensor is one thing. It’s harder to identify who is committing intellectual property theft online. Information does not travel linearly around the Internet. When a consumer buys something online, for example, that data may be routed through several locations before reaching the retailer. Bad actors can leverage the Internet’s routing structure to preserve a degree of anonymity.

“The Internet allows people to mask their location, their intent, and their identity, and to pretend to be someone else,” said Chris Hoofnagle, a professor at the UC Berkeley School of Information.

There are enforcement options. Hoofnagle points to “intermediaries” as places where intellectual property theft enforcement can be successful. Services that people use to conduct business on the Internet, like cloud services and payment providers, can thwart thieves by banning them from their platforms.

“The Internet is largely a winner-take-all marketplace, so at the end of the day, there are a limited number of payment companies and registrars being used, and they tend to be really big companies,” Hoofnagle said.

Estimating Damages

The Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, a bipartisan commission that assesses the impact of intellectual property theft, struggles to estimate damages for the same reason that makes intellectual property easy to steal: the ability of intellectual property to be copied and distributed widely. The ODNI’s 2015 estimate of $400 billion is conservative. Opportunity cost would increase that figure. But Weber believes the debate over the cost of intellectual property theft misses the point.

“The real point is about the long-term competitive consequences of not being able to protect IP in a way that actually incentivizes innovation,” he said, “and [assures] an adequate return to the people who developed the IP.”

Weber said there’s the danger of a chilling effect: “What intellectual property is not being created because it’s too easy for others to steal?”

View the text-only version of Intellectual Property Theft at Scale.

Citation for this content: cybersecurity@berkeley, the online Master of Information and Cybersecurity from UC Berkeley.